Planning in India and the Five-Year Plans significantly influenced the Indian Economy from 1951 to 2017. Planning in India was overseen by the Planning Commission, designed to elevate India to a status of industrialization and economic autonomy. Leaders under this system included a nominated deputy chairman, such as Montek Singh Ahluwalia, who served until the commission’s dissolution in 2014.

The allocation of India’s resources was informally structured until the Fourth Plan, lacking clear processes for distribution amongst states. This approach led to the Gadgil formula’s establishment in 1969. It aimed to ensure fair allocation of central assistance to state plans. Subsequently in 2014, the dissolution of the Planning Commission was declared, marking the inception of the NITI Aayog, which stands for National Institution for Transforming India.

Econometrics Tutorials with Certificates

Introduction to Five-Year Plans in India

Five-Year Plans (FYPs) represent intricate, centralized, and comprehensive economic strategies implemented at the national level. Originating under Joseph Stalin’s leadership in the Soviet Union circa 1928, they proliferated to encompass communist and also some capitalist nations. Henceforth, India initiated its inaugural First FYP in 1951, post-independence. This approach, therefore, reflected India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s socialist inclinations and priorities.

Origins and Purpose of Five-Year Plans

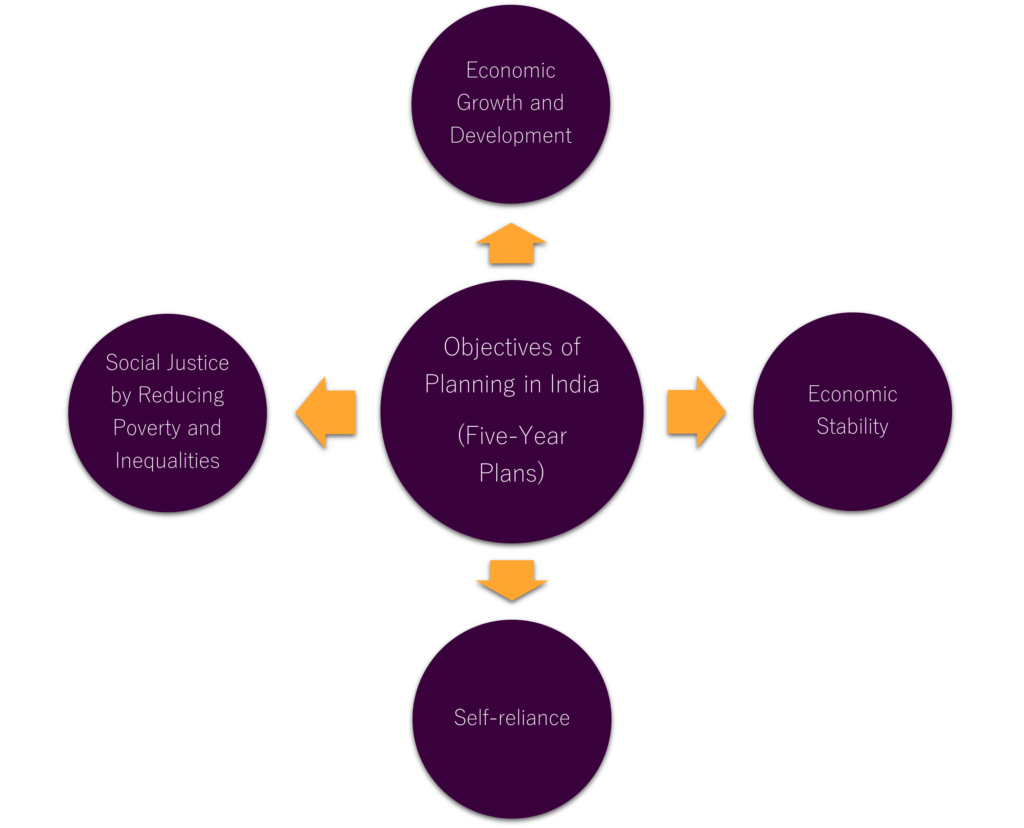

The primary aspirations of India’s planning endeavours included augmenting the real national income twofold within two decades and further achieving parallel growth in per capita income in 25 years. With these goals in mind, the country adopted a centralized economic model, focusing on accelerating industrial growth, enhancing infrastructural foundations, and also bolstering social welfare initiatives. The core strategy to realize these objectives involved disciplined investment, meticulous resource allotment, and strategic policymaking across the economic landscape.

Vision for Economic Development

In designing the Five-Year Plans, a prominent socialist vision underpinned the strategy, further accompanied by an ardent quest for self-sufficiency in economic growth. Endeavouring to metamorphose into a sophisticated, dual-focused industrial and modern economy, the plans gave precedence to empowering heavy industries, fortifying the defence sector, and advancing the concept of import substitution. Moreover, the overarching centralized planning framework aimed to mitigate the nation’s socio-economic disparities, fostering an even, equitable development trajectory that encompasses all strata of society and geographies.

First Five-Year Plan (1951-1956)

In 1951, India embarked on an ambitious journey, launching the First Five-Year Plan. It focused primarily on bolstering the primary sector. Resources worth ₹2,069 crore, later augmented to ₹2,378 crore, were distributed across seven key domains. Notably, substantial investments were earmarked for irrigation, energy, agriculture, community development, transport, and communications.

Moreover, this endeavour sought to address the challenges posed by national partition and the aftermath of World War II. Simultaneously, it aspired to build the cornerstone for the country’s industrial and agricultural growth. Additionally, projects in the irrigation sector, notably the initiation of Bhakra, Hirakud, and Damodar Valley dams, marked this period.

Establishment of Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs)

Culminating in 1956, the First Five-Year Plan’s impact was significant. It also witnessed the foundation of five Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs). These institutions played a pivotal role in the technical advancement of the nation.

Successful Economic Growth and Achievements

The plan was a resounding success, surpassing growth targets. Achieving a 3.6% annual GDP growth, it exceeded the anticipated 2.1%. Furthermore, per capita income saw an 8% augmentation during this period. However, rapid population growth led to a scenario where the national income overtook the per capita income.

Second Five-Year Plan (1956-1961)

An intensive focus on the public domain and a fervent drive towards industrial modernization characterized the Second Five-Year Plan. Furthermore, tt adhered to the principles of the Mahalanobis model, a developmental roadmap by the esteemed Indian statistician, Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, crafted in 1953. This model aimed to judiciously distribute investments across sectors to propel enduring economic expansion.

A collaborative effort saw the inception of hydroelectric endeavours and the establishment of five steel enterprises in regions like Bhilai, Durgapur, and Rourkela, supported by nations such as the Soviet Union, Britain, and West Germany, correspondingly. Coal output as well as the expansion of railway networks in the northeastern frontier recorded noteworthy enhancements. The financial allotment for this phase reached Rs. 48 billion, spanning critical areas like power generation, irrigation, and social and transport infrastructures.

Third Five-Year Plan (1961-1966)

The Third Five-Year Plan’s primary focus was on bolstering agriculture, notably aiming to increase wheat production. This was the advent of the Green Revolution in India. However, the short but impactful Sino-Indian War of 1962 laid bare substantial economic vulnerabilities. This conflict prompted a significant reorientation, elevating defence industry development and the bolstering of the Indian Army. This shift was further compounded in 1965 when India engaged in armed conflict with Pakistan.

Simultaneously, 1965 marked a critical juncture as India faced a severe drought, ushering in a period of inflation. Consequently, the nation pivoted its efforts towards economic stabilization through stringent price control measures. Infrastructure development, particularly the construction of dams, saw sustained progress. Moreover, the era witnessed the establishment of numerous key industries including those focused on cement and fertilizer production.

Punjab, specifically, gained recognition for its significant contributions to the country’s wheat stockpile. Noteworthy also is India’s debut in seeking financial aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) during this time, which prompted a depreciation of the rupee’s value.

Plan Holidays (1966-1969)

The government, facing the dismal results of the Third Plan, instituted a “plan holidays” policy from 1966 to 1969. Therefore, this era saw the drafting of three annual plans with a combined budget of approximately 1600 crores. In 1966–67, the industrial sector underperformed due to a 2.1% contraction, contrasting with a 3.9% expansion the year before. Agriculture, its supplementary fields, and industry accorded equal weight.

To bolster exports, the Indian government also implemented the “Devaluation of the Rupee” during the Plan Holiday. Moreover, this devaluation was a key strategy to combat the economic challenges besetting the nation. Ongoing wars, resource constraints, and mounting inflation triggered by external conflicts and internal shortages further necessitated this break from conventional economic strategies.

The objective of the Plan Holiday was to mitigate the financial repercussions of the Third Plan’s failure, which sought to achieve a 5.6 per cent economic growth rate. Surprisingly, amidst these challenges, the economy thrived, recording a 6.9 per cent growth rate, significantly outperforming the Third Plan’s anticipated 5.9 per cent increase. By the Plan Holiday’s end, food grain production soared from 72 million to 95 million tons, validating a more optimistic economic outlook.

Fourth Five-Year Plan (1969-1974)

The Fourth Five-Year Plan was a critical stage in India’s economic evolution under the auspices of the Gadgil formula. It centered on arresting the escalation of wealth and economic power imbalances. Through a lens of growth intertwined with stability, the Plan set the course toward increased independence. Indira Gandhi led the nation as Prime Minister, making pivotal decisions such as the Nationalization of 14 significant banks. Simultaneously, in the agricultural sector, the Green Revolution heralded a new era of productivity.

The vision of the Plan was not solely economic but also social, aiming to elevate rural communities by amplifying agricultural output. This approach sought to bolster incomes. Foster growth, and sectors such as transport, machinery, mines, power, and chemicals in the industrial sphere were of primary focus. Yet, the strategies employed were criticized for being overly ambitious, which consequently led to the Plan’s inability to achieve its set objectives.

Central to the Plan’s ambition was a move towards decreasing dependency on foreign financial aid. Emphasizing industrial and agricultural autonomy, the goal was to attain self-sufficiency. Aiming for a growth rate of 5.6%, the Plan realized a growth of 3.3%, demonstrating both ambition and the challenges of execution.

On the geopolitical front, the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 and the subsequent Bangladesh Liberation War significantly impacted the Plan’s industrial development budget. These conflicts necessitated a redirection of resources, affecting the economic trajectory intended by the Plan.

Fifth Five-Year Plan (1974-78)

The Fifth Five-Year Plan placed significant emphasis on employment creation, the eradication of poverty through the ‘Garibi Hatao’ mission, and ensuring justice for all. Moreover, achieving self-sufficiency in the agriculture and defence sectors was of crucial focus. However, the scheme met opposition when the newly inaugurated Morarji Desai administration rejected it in 1978. In 1975, a crucial amendment to the Electricity Supply Act was made, granting the central government authority in power generation and distribution.

Shift Towards Poverty Alleviation and Employment Generation

The objectives of the Fifth Five-Year Plan included the creation of 50 lakh jobs and also a reduction of the population growth rate to around two per cent yearly. Moreover, tt aimed to lift 22 per cent of the populace out of poverty by its culmination. Throughout the plan, the economy posted an impressive annual growth of about six per cent.

Major accomplishments of the plan encompassed the amelioration of inflation, enhancement of the nation’s balance of payments, and a significant surge in the investment rate. Agricultural output also experienced robust growth. Consequently, the standard of living saw an upturn, along with amplified employment opportunities. The plan also played a vital role in promoting social equity and fulfilling the essential needs of the citizens. Additionally, the period witnessed substantial advancements in infrastructure and quality of life, attributed to the plan’s efforts.

The Rolling Plan (1978-80)

The Morarji Desai government abandoned The Fifth Five-Year Plan. They introduced the Sixth Five-Year Plan which was again abandoned in the 1980s by the Indian National Congress Government. This “Rolling Plan”, therefore, spanned from 1978 to 1980. Under this plan, the budget was included for the present year, a plan for the next 3, 4 or 5 years and also a long-term plan for the next 10, 15 or 20 years.

The advantage of this approach was that the plans were flexible and could be amended based on the needs of the economy. On the other hand, the major disadvantage of this approach was that it became difficult to achieve the set objectives since they were changed or revised each year.

Sixth Five-Year Plan (1980-1985)

The Sixth Five-Year Plan encompassed a concerted push to elevate national income, enhance technological standards, and incrementally shrink the spectres of poverty and unemployment. The orchestration of multifaceted programs such as TRYSEM, IRDP, and NREP was instrumental in achieving these objectives. As a result, the plan outpaced its economic growth projection, securing a 5.7% surge against the envisioned 5.2%.

Focus on Modernization and Technology

A primary vanguard for the Sixth Five-Year Plan was the imperative of modernization and technological elevation across economic domains. Its directive involved the catalysis of resource efficiency, the amplification of productivity, and the advent of indigenous energy sources. Further pursuits aimed to abate regional disparities and inequities within income and wealth distribution.

Poverty Alleviation Programs

Concurrently, abating poverty and fostering employment gained paramount focus within the Sixth Five-Year Plan’s structure. Initiatives like TRYSEM, IRDP, and NREP were set in motion. These programs aimed at furnishing vocational skills, executing rural development schemes, and carving job avenues for marginalized sectors of society. As a result, a significant dip in the poverty ratio, from 48.3% (in 1977-78) to 36.90% (at the culmination of 1984-85) signalled the fruition of these endeavours.

The Sixth Five-Year Plan’s quantitative approach to advancing economic frontiers, technological sophistication, and ameliorating poverty stands as a hallmark moment in India’s narrative of all-encompassing evolution.

Seventh Five-Year Plan (1985-1990)

The Seventh Five-Year Plan had ambitious goals. It sought to boost food grain production, create more jobs, and enhance productivity across the board. Its core focus was on the essentials: ‘food, work & productivity’. Impressively, the plan exceeded expectations, propelling the economy to a 6% growth, surpassing the 5% target.

Emphasis on Food Security and Productivity

India aimed to uplift both industry and agriculture during this period. It also sought to improve economic efficiency across the board. There was a clear call to enhance the operational efficiency of the economy, especially in terms of food production and rural progress. Over the plan’s duration, food production rose by an astounding 2.8% annually, outstripping the population growth’s 2%. This was pivotal for India, underlining a strategy of boosting foodgrain output and tackling rural developmental issues head-on.

Economic Liberalization Initiatives

Though it had its triumphs, the plan fell short on many objectives, hamstrung by widespread corruption unaddressed at governmental levels. A failure to adapt to the nation’s swiftly evolving demographics, resulting in burgeoning unemployment rates compounded this struggle. Nevertheless, industrial production witnessed a significant surge, accompanied by advancements in education, healthcare, and public infrastructure.

The Annual Plans (1990-92)

In 1990, the Eighth Five-Year Plan faced delays due to growing political instability at the nation’s core. As a result, the years 1990-91 and 1991-92 evolved as critical annual plans. These periods also laid the vital groundwork for economic reforms. Such reforms encompassed seminal structural adjustments, crucial for the eventual rollout of the Eighth Plan in 1992.

| Key Economic Indicators during and after the Annual Plans (1990-92) |

|---|

| GDP growth rate in 1992-93: 4.0%, compared to 1.1% in the previous year |

| Estimated GDP growth rate for 1993-94: 3.8% |

| Agricultural production improved by 4% in 1992-93, with foodgrain production reaching 180 million tonnes, a 7% increase over the previous year |

| Index of industrial production showed a modest growth of 1.6% during April-October 1993-94 compared to the same period in the previous year |

| Inflation rate during 1991-94 averaged around 10%, with the rate for April-Dec 93 being 7.8%, lower than the previous years |

| Current account deficit reduced to 1% of GDP in 1991-92 but rose to 2.2% in 1992-93 |

| Private sector involvement increased, particularly in power, oil, transport, and telecommunication, with a focus on motivating private investment in infrastructure during the period covered |

These annual plans functioned as a crucial bridge period, ushering in the Eighth Five-Year Plan development in 1992. This process was directly derived from the launch of economic reforms, structural adjustment policies and the New Economic Policy of 1991.

Eighth Five-Year Plan (1992-1997)

The inception of the Eighth Five-Year Plan in 1992 closely followed the introduction of structural adjustments and economic overhauls known as the New Economic Policy of 1991. It marked a pivot towards a market-driven model, significantly elevating the role of the private sector and enticing foreign direct investments. The earmarked growth figure was 5.6%, yet the achieved growth surpassed this envisaged target, resting at approximately 6.8%. For this plan, an estimated allocation of 798,100 crores was made, dedicating 434,100 crores to public sector endeavours within India.

In its pursuit, agriculture and related sectors endeavoured for a 3.5% growth, eventually attaining 3.9%. The initial momentum was robust, with an average growth of about 7.7% in the earliest phases of the plan. Notable initiatives introduced during this period encompassed the “Mid Day Meal Scheme,” “Indira Mahila Scheme,” “The Ganga Kalyan Yojana,” “Mahila Samridhi Yojana,” and “The Pradhan Mantri Rojgar Yojana.”

Ninth Five-Year Plan (1997-2002)

The Ninth Five-Year Plan saw a decline in focus on the public sector. Hence, it shifted towards supporting the private sector and foreign investment. This change was further motivated by a negative trend in savings within the government and public sectors. It highlighted the need for the private sector to play a significant role in driving economic growth.

During its term, the Ninth Five-Year Plan worked to meet social and human needs. It aimed to raise income levels and enhance living standards. Unfortunately, the plan period witnessed a growth in disparities, especially between the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. This led to noticeable income inequalities. Addressing unemployment emerged as a crucial challenge, affecting both rural and urban areas. The plan found it difficult to create enough job opportunities.

The primary goal was to provide essential services and employment. The plan also aimed at reducing disparities prevalent across regions and social strata. It laid particular stress on agriculture, seeking to elevate its growth rates and enhance productivity. Diversification into related fields such as animal husbandry and horticulture was encouraged.

Strategies in rural development were designed to boost infrastructure and agricultural productivity. This included expanding off-farm activities and job opportunities in rural areas. Therefore, the investment was directed towards improving rural infrastructure with a focus on roads, irrigation, and educational and healthcare facilities.

Tenth Five-Year Plan (2002-2007)

The Tenth Five-Year Plan aimed at fostering robust economic growth with the prime objective of ensuring even distribution of developmental benefits, thus advancing inclusive development. The plan aspired for a sustained annual growth of 7.7%.

The industrial and service sector forecasts were not met. Weak performance of the agricultural sector, infrastructural bottlenecks, and low rates of urbanization were the reasons behind this shortfall. The plan also aimed to reduce poverty by 5% and decrease the gender gaps in literacy and wages by 50%.

The overarching goal of the Tenth Plan was to achieve an annual GDP growth of 8%, aiming to double the per capita income. For the years 2002 to 2007, a requisite GDP growth rate of 8.0% was set, outlining the strategic economic development objectives for the time span and a growth rate of 7.7% was achieved.

Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007-2012)

The Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007-2012) underscored the imperative of inclusive growth and development. Its focal points included the enhancement of the social sector, rural infrastructure, and the advancement in access to superior education and healthcare services. The scheme identified imperatives within the domain of clean energy technologies, underscoring the momentum of wind power, solar applications, and other eco-friendly solutions.

Its vision extended to the electrification of all villages, offering complimentary household connections to 2.3 crore BPL households through the RGGVY scheme. Moreover, the Plan ardently strived to proliferate newer energy systems, emphasizing access to renewable and cleaner energy sources. Vital initiatives within nuclear power, bioenergy, and bioremediation were spotlighted, affirming the commitment to innovation in energy technology.

The Eleventh Five Year Plan was distinguished by its sharp focus on inclusive growth and social sector development. An expression of governmental commitment, it sought to ensure widespread and equitable progress, striving to uplift the standard of living for all. Its target growth rate of 9%, achieved 8%, underlines its commitment to accelerated advancement.

The plan’s financial outlay noticeably surged, from 8,10,400 crore in the 10th five-year span to 14,21,711 crore during its tenure. It registered significant accomplishments, such as curbing the trade deficit and fertility rate, and dedicated efforts towards parity in gender representation. It accorded precedence to agriculture, service, and industrial sectors, with pronounced attention to skill development, education, and promoting environmental well-being as cornerstones of sustainable development.

Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012-17)

The Twelfth Five-Year Plan, active from 2012 to 2017, marked the closure of the traditional Planning Commission era and the inauguration of NITI Aayog. This stage witnessed the urgent shifts in economic priorities and the dynamic challenges confronting India. Significant transformations in the planning mechanisms and their respective management bodies characterized this period.

Evolving Economic Priorities and Challenges

During the formulation of the 12th Five Year Plan, a growth ambition of 8% was established at a high-level National Development Council (NDC) gathering in New Delhi. Yet, the then Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, Mr. Montek Singh Ahluwalia, cautioned against a higher target. He iterated that hitting an average growth of 9% within this timeframe was not realistic, leading to a moderated target range of 8% to 8.5%.

The strategy for the 12th Plan included a focused initiative to diminish the poverty level by 10%. Notably, there was a considerable acceleration in the poverty reduction pace during the preceding plan, that is, the Eleventh Five-Year Plan.

Resembling a blueprint, a commitment was made for real GDP to elevate by 8% annually throughout the Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012-17). In tandem, the aspiration to lower the poverty quotient by 10% was laid out, featuring targets for agriculture to grow by 4% each year.

The administration laid out aims of creating 5 million fresh roles and endorsing non-farm competencies to arrest employment dilemmas. In the domain of education, the objectives included extending the average schooling years to seven and facilitating the addition of 20 lakh seats for higher education for each demography group. The health directives highlighted ambitious targets to decrease infant and maternal mortality rates, along with enhancing the child-sex ratio.

Notable environmental commitments were made to augment greenery by a million hectares annually and to substantially reduce child malnutrition through TFR adjustments. It also included ambitious service benchmarks like extending banking facilities to 90% of families. Furthermore, it targeted universal electricity access, lower power losses, enhanced road connectivity, and increased telecommunication access in rural sectors, envisaging a 70% teledensity.

Conclusion

India’s Five-Year Plans stand as pivotal pillars in the nation’s economic growth post-independence. These ambitious, nationwide schemes have swiftly responded to dynamic economic and political shifts, surviving adversities like wars, natural disasters, and economic limitations. Their impact resonates through India’s profound strides in industrial growth, agricultural advancements, and bolstering social welfare.

Initiated in 1951, the maiden First Five-Year Plan set a target of 2.1% annual growth, which it surpassed by achieving 3.6%.

The subsequent Second Plan pivoted towards industrial expansion, while the following Third Plan aimed for a robust 5.6% growth rate but was impeded by the Indo-China conflict and rupee devaluation. Undeterred, the Fourth Plan endeavoured for self-reliance in food production, yet it managed only a 3.3% growth, falling short of its 4.4% objective.

With aspirations to diminish poverty, elevate job availability, and foster agricultural self-dependence, the Fifth Plan boasted a commendable 4.8% growth, outpacing its 4.4% target. These endeavours highlight the efficacy and resilience of India’s long-term economic strategies.

Continuing, as India’s economic landscape evolves, the strategic planning processes must adapt. This evolution is essential to sustain the nation’s growth momentum and development, focusing on the critical sectors of economic progress, policy implementation, and overcoming challenges.

Econometrics Tutorials with Certificates

This website contains affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.